back to top

1. LATE INVOICES

back

to top

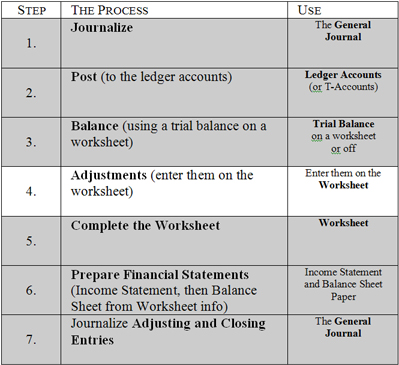

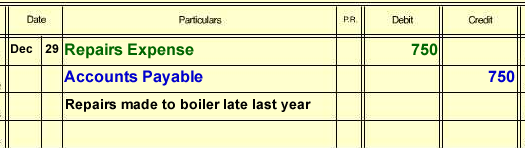

We will begin by looking at the concept of the late invoice.

On January 10th, of this year, we received a purchase

invoice from J. Simmons Inc. for repair services that were done on December

29th of last year.

This is a late invoice requiring an adjustment. The journal

entry to record this adjustment is the same as it would be if the invoice

arrived on time.

2.

ACCRUALS

back

to top

Accruals are something that build up or accumulate. All

that is necessary for an accrual to be earned or incurred, is FOR THE PASSAGE

OF TIME. We will examine the following four types of accruals:

a. Prepaid Expenses

b. Unearned Revenues

c. Interest

d. Salaries and Wages

a. Prepaid Expenses

back

to top

In some cases it makes sense for a company to pay in

advance for routine expenses it has every month. This can save time and money.

Examples include Rent and Insurance.

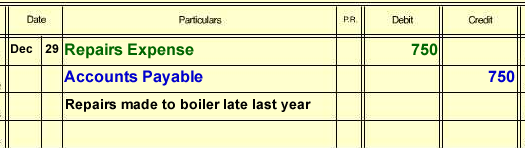

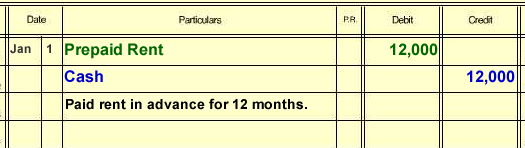

Example: A company that pays rent of $1,000 a month,

pays for its rent for a full year in advance on January 1st of this year.

The journal entry would look like this on January 1st.

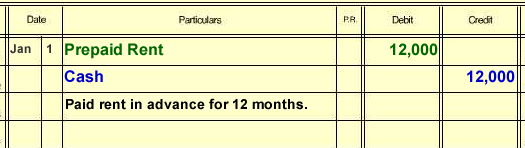

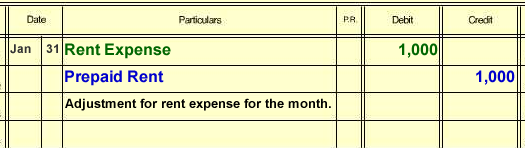

However, on January 31st, one month’s worth of

rent has been used up (i.e. one’s month’s worth of rent expense

has accrued). If

this company were preparing adjustments at the end of January, the entry to

adjust prepaid rent would be:

($1,000 of rent is what the company pays each month)

Note: with every expense a company prepays, there will

be two corresponding accounts:

1. The prepaid expense

account – this is a current

asset as it hasn’t been consumed yet (because if the company

moved for example, they’d get it back)

2. The expense account –

as the expense accrues,

value is moved from the prepaid account to the expense account. All that

is needed for these expenses to accrue is for time to pass.

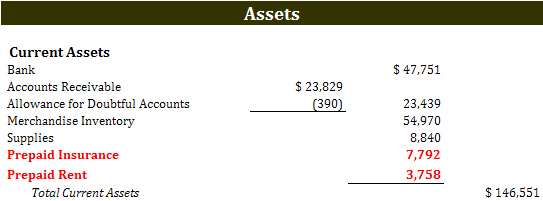

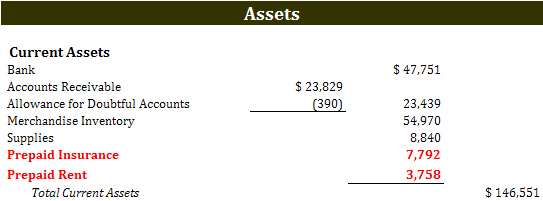

A prepaid expense

usually appears on the balance sheet right after supplies and any inventory

items as show below.

back

to top

b. Unearned Revenue

back

to top

Unearned

revenue is very similar to prepaid

expenses. For every revenue item that is prepaid by a customer, a business

will also have two accounts:

1. The unearned revenue

account – this is a current

liability account (again, because if you end up not earning the revenue,

you have to give the prepaid funds back to the customer)

2. The revenue account

– where the liability goes once the revenue has been earned.

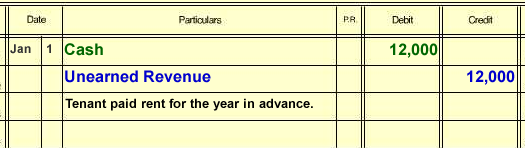

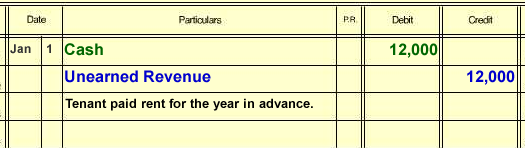

If we return to our example of prepaid rent, we will

now examine what our prepaid rent looks like in the accounts of the landlord.

On January 1st when we prepaid the year’s rent

of $12,000, the landlord would have recorded the following transaction:

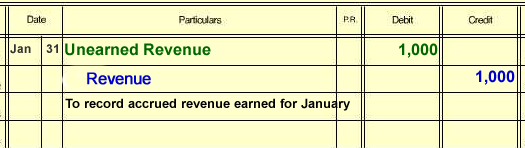

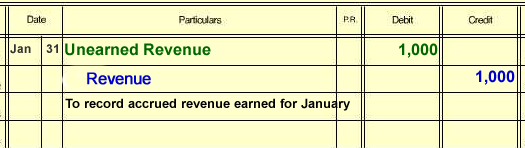

Then, at the end of the month (if the landlord does adjustments

then), when we showed an accrued

rent expense of $1,000, the landlord would record the following transaction

to show accrued revenue:

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your own first!

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your own first!

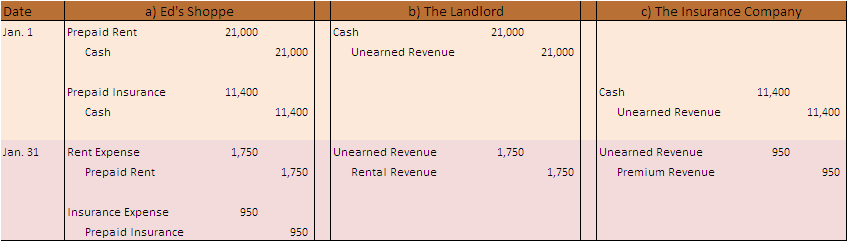

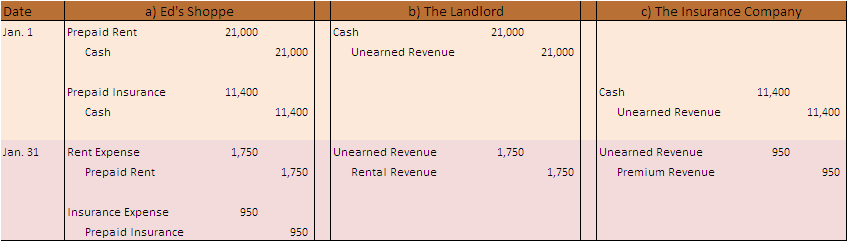

Ed’s Shoppe pays rent of $1,750 per month, and

pays business insurance premiums of $950 per month. If Ed’s Shoppe

pays for these costs for a year in advance on January 1st of this year,

make the entry on January 1st to record the payment, and on January 31st

to record the adjustment for:

a) Ed’s Shoppe

b) The Landlord

c) The Insurance Company

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

back

to top

c. Interest

back

to top

Interest is the

price of money; it is the cost of borrowing funds. It is stated as a percentage

cost on a yearly basis, however, it is usually paid monthly.

For example, 4% interest means to borrow $100 it would cost you $4 per year.

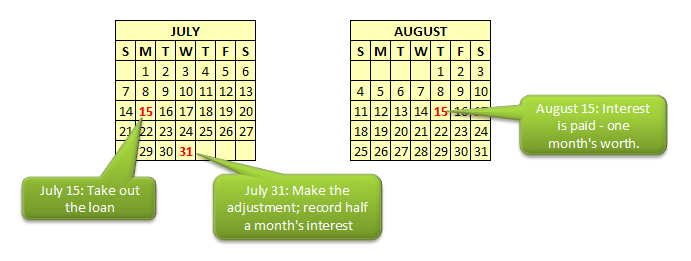

Like other accruals, all that has to happen for interest

to accumulate is for time to pass. The problem is that interest is paid at

fixed points in time (say, the 15th of the month). However, this date may

not necessarily correspond to the end of your accounting period, which may

be the 31st of the month.

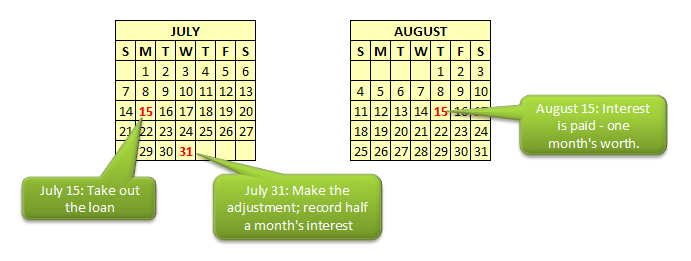

Observe:

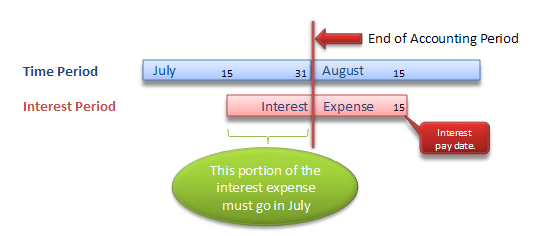

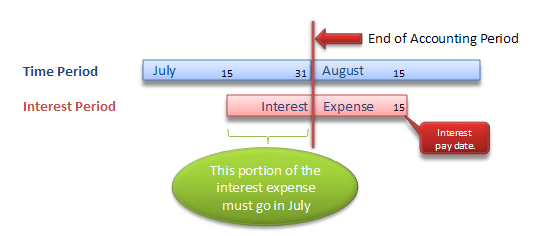

The reason can also be shown visually as follows:

Since half the interest period falls in July, half the

interest expense must be recorded in July.

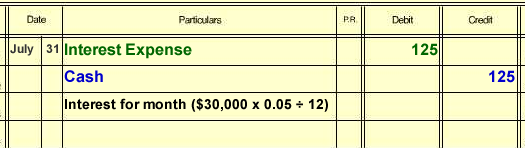

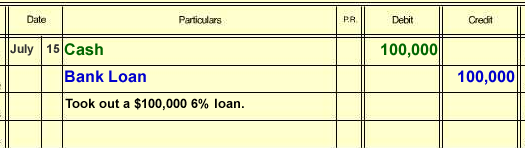

In the images above, assume our company acquired a $100,000 Bank Loan at 6%

interest on July 15th. We must make adjustments

for interest accrued

(but NOT PAID)on July 31st at the end of our

accounting period, and we are required to pay our first month's interest payment

of $500 on August 15th, one month later. ($100,000

x 0.06 ÷ 12 = $500)

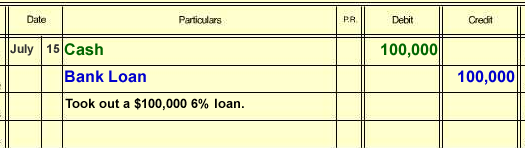

The entry to show us acquiring the loan is as follows.

If our accounting period ends on July 31st, no interest payment will have

been recorded. However, July 31st is half way to our first interest payment,

therefore we have accrued

half of that interest expense and the entry would be as follows:

Note: no cash is paid on this date. This is because the

interest payment is not due on July 31st. It isn't due until August 15th.

Only the obligation to pay is recorded on the July 31st adjustment date.

On August 15th, our first interest payment is made. We must record the interest

earned from August 1st to August 15th (we only recorded half a month above,

the other half must now be recorded). We must also pay the interest. The entry

looks like this:

Now take a look at these same events and compare them

with the books of the bank from which you borrowed the money. You'll see that

an interest expense to us, is interest revenue to a bank. Interest to be paid

(payable) is interest to be received by the bank. Observe:

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your own first!

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your own first!

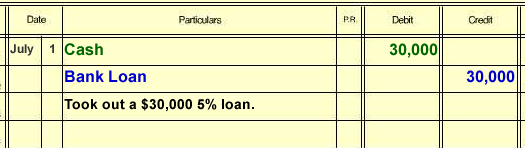

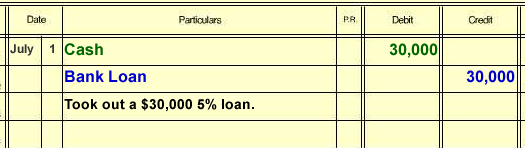

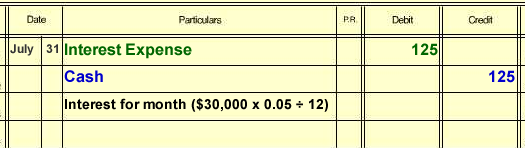

XYZ Inc takes out a loan on July 1st for $30,000

at 5% interest per year. Record the entry on July 1st, and the adjusting

entry on July 31st.

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

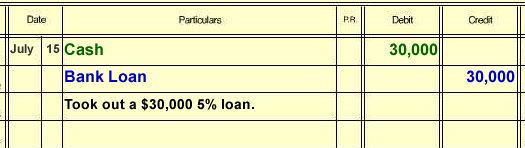

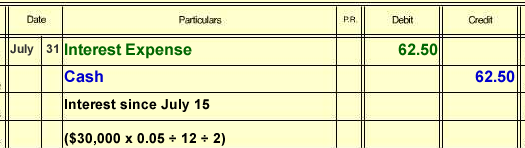

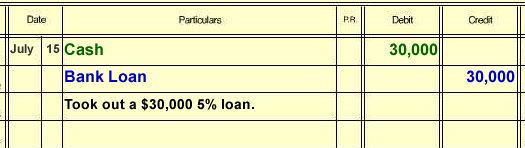

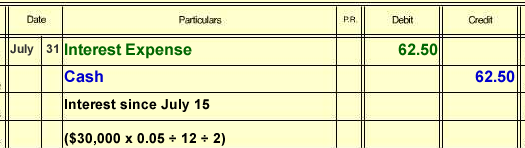

Now what happens if a loan is taken out on a day other

than July 1st? Assume now, that XYZ Inc takes out a loan on July 15th for

$30,000 at 5% interest per year. Record the entry on July 15th, and the

adjusting entry on July 31st.

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Note how there is no payment on July 31st this time.

The first interest payment is due at the end of the 30 day period after

the loan was taken out. That is August 15th, not July 31st.

back

to top

d. Salaries

and Wages

back

to top

Note: salaries

and wages are not

the same thing. Wages are based on how many hours you work, salaries are generally

fixed.

However, salaries and wages work in a similar fashion

to interest. As

employees earn their pay, a company earns a salaries or wages expense. If

employees have earned money but haven’t been paid on the last day of

the accounting period, an adjustment must be made.

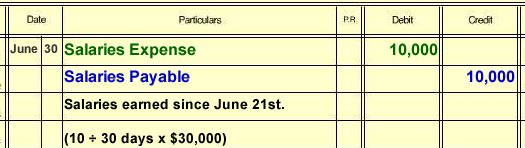

Example: Employees are paid every two Wednesdays. In

this example, the last pay day was July 24th. The events evolve as follows

in the image below:

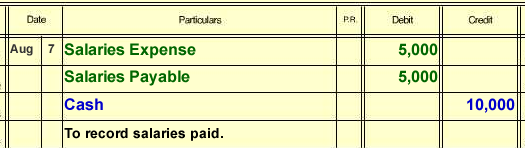

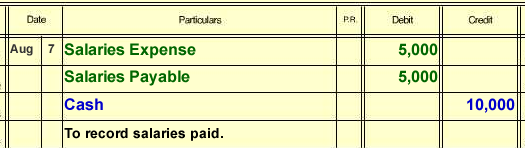

If the salaries expense every two weeks is 10,000, then the journal entry

on July 31st would recognize one half of the regular salary expense. (It’s

half way through the pay period). However, it’s not a pay day, so no

payment would be made. Observe:

On August 7th, we would pay employees the regular amount,

and record the second week’s salary expense.

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

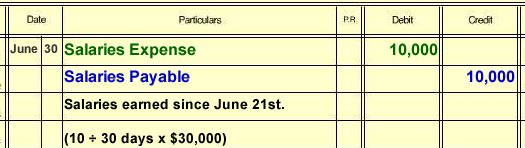

Salaries of $30,000 are paid on the 21st of each month.

Record the adjusting journal entry on June 30th.

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

back to top

3. ALLOCATIONS and AMORTIZATION

back

to top

Allocations

and amortization

are the conversion of asset value into expense. They are done to make the

accounting records more accurately reflect what is happening, but there is

no magical way to get a 100% accurate value. They are estimations; they are

guesses, and they are arbitrary in many ways. There are, however, set methods

of coming up with the adjustment value.The following three types will be examined:

a. Bad Debt

b. Supplies

c. Amortization

i The Straight-line method

ii The Declining balance method

So, what is an allocation?

When we're talking about cost, "allocating"

means taking some of the value of an asset and turning it into an expense

in the period using a prescribed method (such as the straight-line

method of amortization).

This cost allocation

may or may not truly reflect how an asset’s value is expiring over time.

Before we look at our three types of allocations, we

must start with the concept of the contra-account.

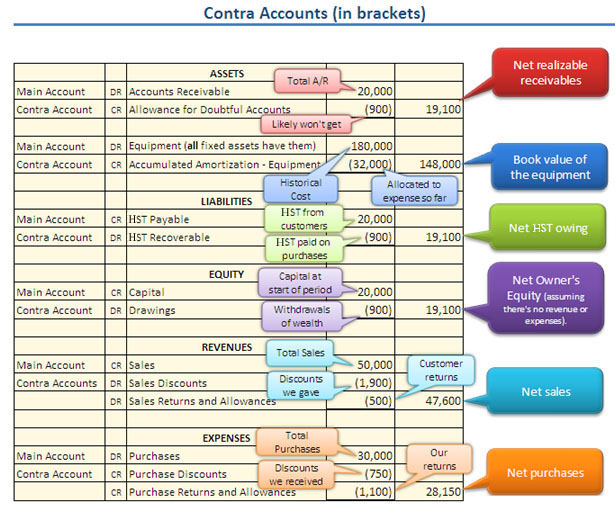

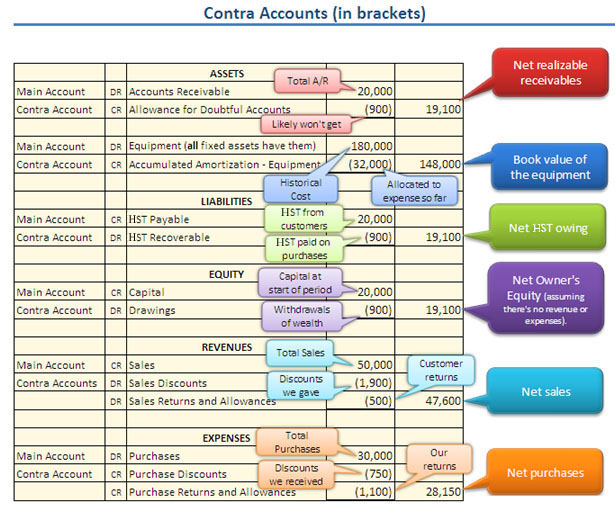

Contra Accounts

Contra

accounts receive their name from the fact that they act in a contrary

manner to the accounts with which they are associated.

You already know one contra account: it’s the drawings

account. Recall how to record a drawings of cash by the owner:

A contra account is shown together with its main account on the financial

statements. When added together, the two accounts produce the total net value

for that account. The concept of the contra account (and its associated account)

is important, because there are adjustments that are involved with a number

of them.

Below is a list of all the contra accounts you’ll

encounter in this course.

back to top

a. Bad Debt

back

to top

Our first allocation

is bad debt. Part

of the cost of selling on credit is acquiring bad debt – that is –

customers who do not pay.

To ignore that some of your accounts receivable will

not be collected is to mislead the users of your financial statements. You

would be telling them that you expect to collect all of your accounts receivable,

when really, you know you will not. Therefore an allocation for bad debt must

be made. It is an adjustment.

There are two steps in the bad debt

process:

1. Make an allowance

as soon as there is a possibility that customers may not pay. This is

when you recognize the expense.

2. Remove the accounts receivable

when you are sure they will not pay.

There are three accounts involved with

Accounts Receivable:

1, Accounts Receivable

(an asset)

2. Allowance for Doubtful

Accounts (a contra-asset - this offsets Accounts Receivable)

3. Bad Debt Expense

(an expense - to show the loss from customers not paying)

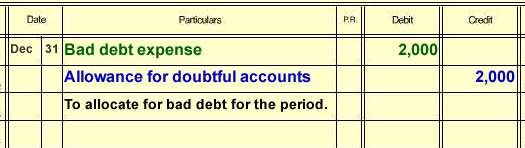

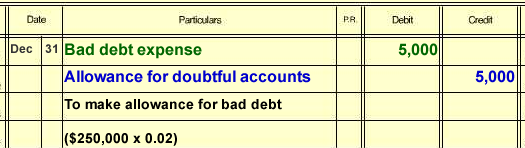

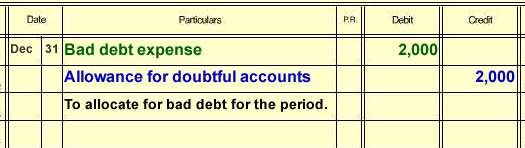

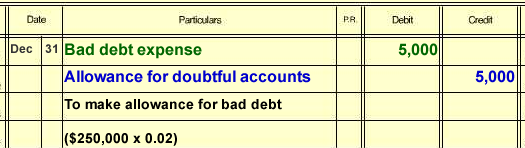

Assume a company made $100,000 of sales on credit in

the current year. Historically speaking, this firm has encountered bad debt

at a rate equal to 2% of net sales on credit. The senior accountant thinks

that history will repeat itself, and orders an allowance of 2% of net sales.

(2% x $100,000 = $2,000). This is step 1 above.

The entry to record the adjustment for step

1 is:

This insures that the cost of bad debt is recorded in the period with the

sales from which the bad debt originated; this adheres to the Matching Principle.

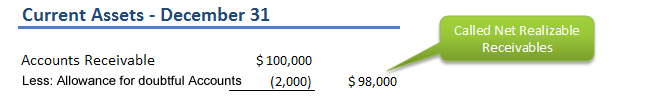

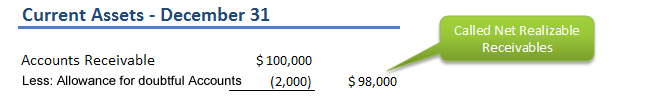

After this first adjustment, the presentation of Accounts

Receivable on the Balance Sheet would look like this (assume we didn't collect

any of our $100,000 in credit sales).

See how we are no longer showing $100,000 as our expected

Accounts Receivable? This would be misleading to do when we know that we likely

won't collect all of them; it's not realistic. Instead, we expect - on average

- to collect only $98,000.

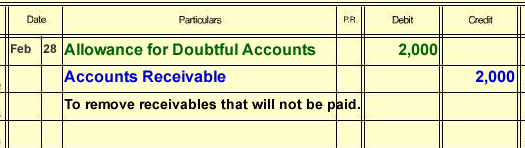

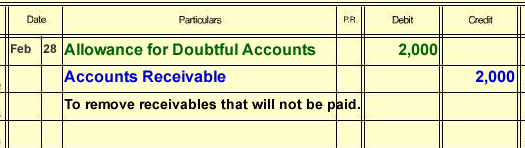

Later on, once the accountant is certain the delinquent

accounts will not be paid, step 2

is carried out and they are ‘written off’ as follows:

Notice how no expense is recorded above

when the accounts receivable is written off. It was recorded earlier when

you first thought you'd have bad debt and made the allowance. This places

the actual expense in the period when it was really earned (i.e. when you

made the bad sale on account to a deliquent customer), and that ensures that

the Matching Principle is followed. You are then free to 'write off' the Accounts

Receivable whenever you feel it is appropriate, with no further effect on

Net Income.

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

Sales on account this year were $250,000, and normally

we experience a rate of bad debt of about 2% of sales on account. Make the

adjusting journal entry for December 31st.

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

back

to top

b. Supplies

back

to top

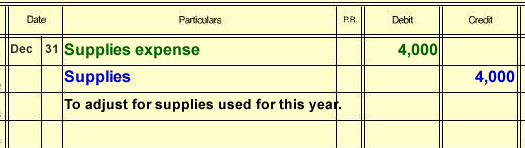

No one creates a source document, and then records a journal entry every time

somebody goes to the supply room and takes a 1¢ pencil. That would be

moronic.

Instead, a count is made (and often is estimated) of

the value of supplies remaining in the storeroom at the end of the accounting

cycle. What’s missing is allocated to supplies expense (even if some

of it may have been stolen and not used in the business).

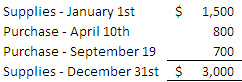

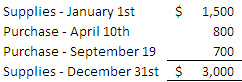

For example, an organization started this year with $1,500

of supplies. They purchased $800 and $700 of supplies at two points during

the year. By the end of the year, the supplies account shows a balance of

$3,000.

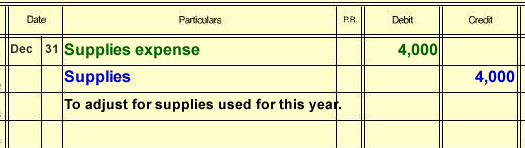

A count was made of the supply storeroom and found that

only $1,200 remained. The journal entry to record the adjustment will be ($3,000

- $1,200 = $1,800):

This entry will record the missing $1,800 as expense,

and lower the value of the supplies account from $3,000 to $1,200, which is

the current level of supplies on hand.

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

Supplies on January 1st were $2,900. Purchases were

made in March, June, and October for $1,000 each month. An inventory count

on December 31st reveals that only $1,900 of supplies remain in the storeroom.

Make the adjusting entry for December 31st.

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

back

to top

c. Amortization

back

to top

What is Amortization?

Amortization

is the allocation

of the cost of a fixed

asset to expense at a pre-determined rate over time. (If you just said

“huh?” read this: Amortization takes value away from a fixed asset,

and turns it into an expense. This is done to reflect the wearing out of the

asset over time.)

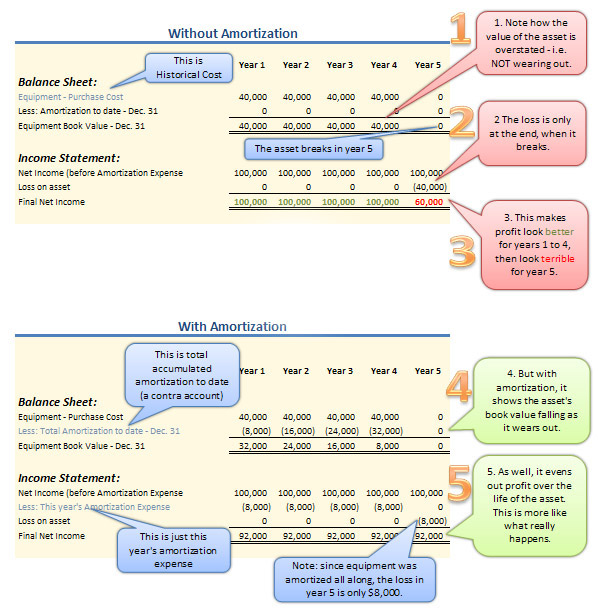

Think about it: if we waited until the day a piece of

equipment broke down for good, before we recorded the loss of that asset’s

total value, we would show an enormous loss in the period that it broke, rather

than showing the wearing out of the asset over time, which is what really

happens.

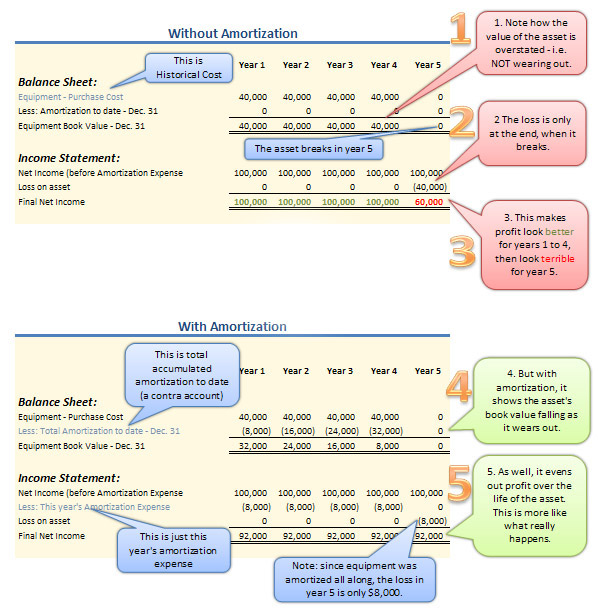

Below is a comparison of a $40,000 piece of equipment

that runs for four years then unexpectedly breaks in year 5. First you can

see how it is reported on the Balance Sheet and Income Statement without

Amortization. Below that you can see what it looks like with

Amortization.

Follow the big orange numbers to examine the comparison

closely.

back to top

How do you amortize?

back

to top

Amortization

is calculated on ALL fixed

assets except land, and must always be up to date on

an asset before that asset is sold or disposed of.

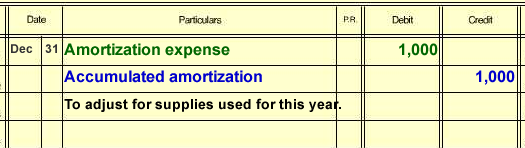

NOTE: The adjusting journal entry for Amortization is

always structured the same. However, there are two methods of calculating

the value of amortization. Both are acceptable under GAAPs. They are:

i. The Straight-line method

ii. The Declining balance method

Regardless of the method above, there are three accounts

associated with every long-term asset (except land) :

1. The Asset Account

- (i.e. Equipment, Machinery, etc.)

2.

Accumulated Amortization - (the contra asset account -

offsets the asset's value)

3. Amortization Expense

- (the expense account)

The expense account is where the value of the asset is

expensed to. The accumulated

amortization account is where you accumulate all the amortization

to date.

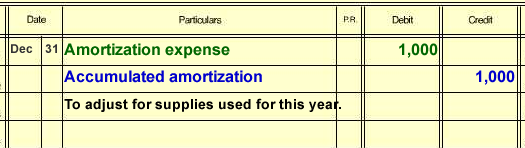

The journal entry is structured like this (every time,

for every long term asset):

NOTE: the original asset account is NOT TOUCHED! All amortization

amounts are accumulated to the contra asset account called Accumulated

Amortization. This is so that a comparison can be made between the original

purchase price, and total amortization to date. The higher the Amortization,

the older the asset. This is important information that would not be revealed

if you removed amortization from the original asset account.

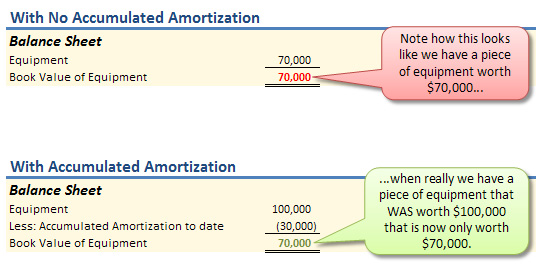

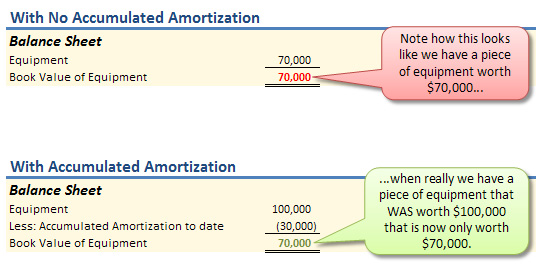

Look at the following comparison for a $100,000 piece

of equipment with $30,000 of accumulated amortization expense over the years:

The difference in size between the original asset account

and the Accumulated

Amortization to date gives us an indication of the age of these assets.

The greater the amortization, the older the assets. This is why we have an

accumulated amortization account. It provides us with valuable information.

back

to top

Amortization:

The Straight-line method:

back

to top

Remember: the journal entry to record the amortization

adjustment is always the same. However, the way of finding the amortization

amount can differ.

The straight-line

method uses the following formula:

Note that this method of amortization will produce exactly

the same amortization expense amount for each year of the asset’s life.

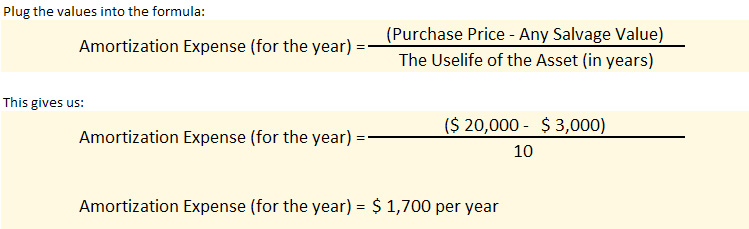

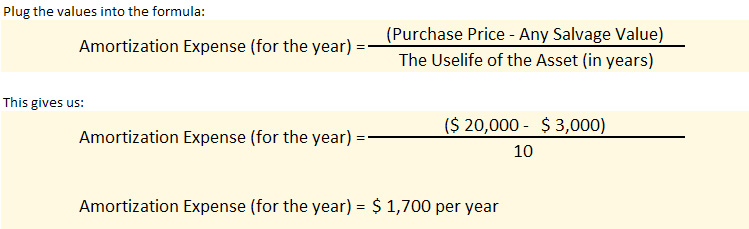

Observe the following:

An asset purchased for $20,000, with a salvage

value of $3,000, and a useful

life of 10 years will have an annual rate of amortization of:

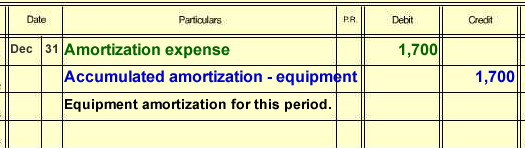

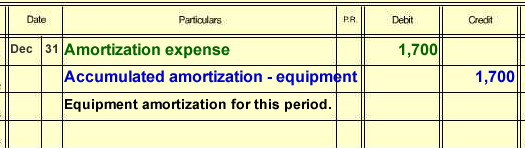

Then record the journal entry as follows (as always):

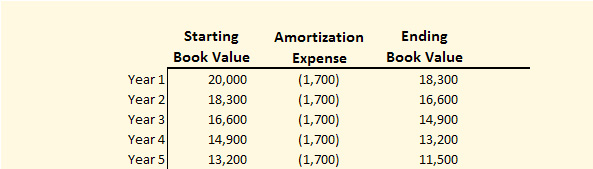

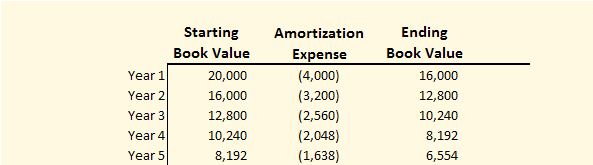

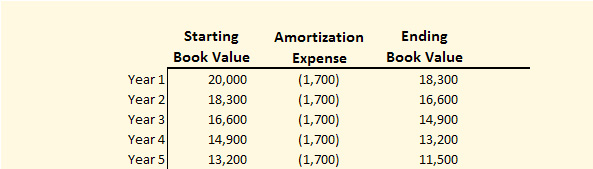

Over five years, its amortization schedule looks like

this:

Note how amortization expense is exactly the same every

year.

back

to top

Amortization: The Declining Balance method:

back

to top

Under the declining

balance method, the same asset will be amortized differently. Remember:

the journal entry to record the amortization adjustment is always the same.

Just the amortization amount will differ.

Let's use the same asset which was purchased for $20,000,

with a salvage

value of $3,000, and a useful

life of 10 years, except this time, we'll say we're going to use an amortization rate of 20% per year. This means it will have an annual rate of amortization of:

Note for declining balance, the amortization expense

will change every year. This is because it is based on a

rate. That rate is multiplied by a continuously falling book

value balance. (Hence the name: declining balance).

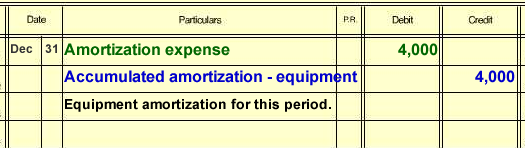

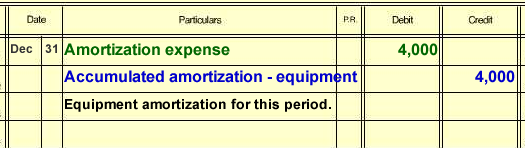

Note though, that to record the journal entry the process

is the same. Only the amount changes:

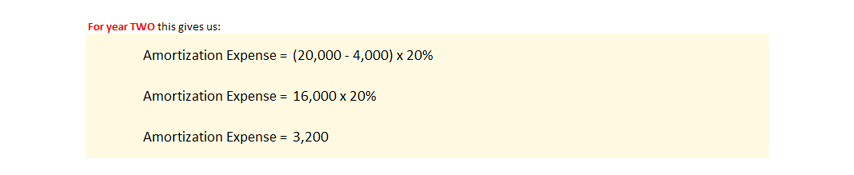

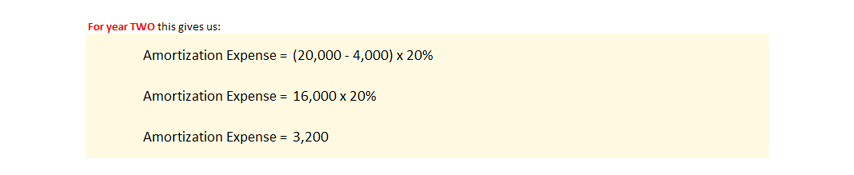

Now, in year two with declining balance, the value changes,

as 20% of a different book value, is a different amount. Year 2 amortization

expense is calculated as follows:

Note how now in year 2 with the declining balance method,

the amortization expense is lower.

The process continues. Each year will produce a different (and smaller) amortization

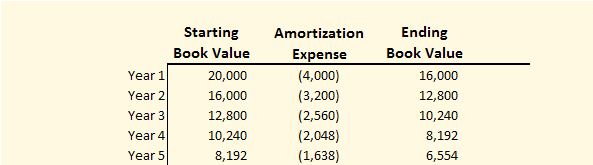

expense. The schedule for the first five years of amortization using declining

balance is:

You can see that Amortization expense falls every year.

Once again, this is because it is based on a constant rate that is multiplied

by a continuously falling book value.

What’s the point?

If you graph the schedules of the two amortization methods,

you’ll notice that straight-line amortizes the equipment evenly, and

declining balance amortizes the asset more quickly in the beginning than in

the end.

Thus, management should select the amortization method that best represents

how they feel the asset will actually wear out over time. For example: a vehicle

loses a large portion of its value early in its life, therefore declining

balance may be the best choice for this type of asset.

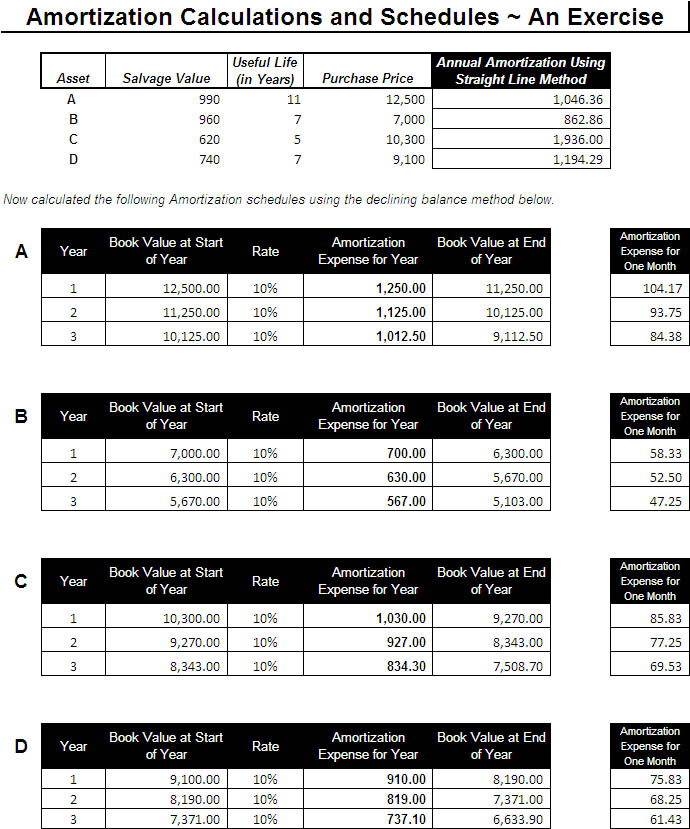

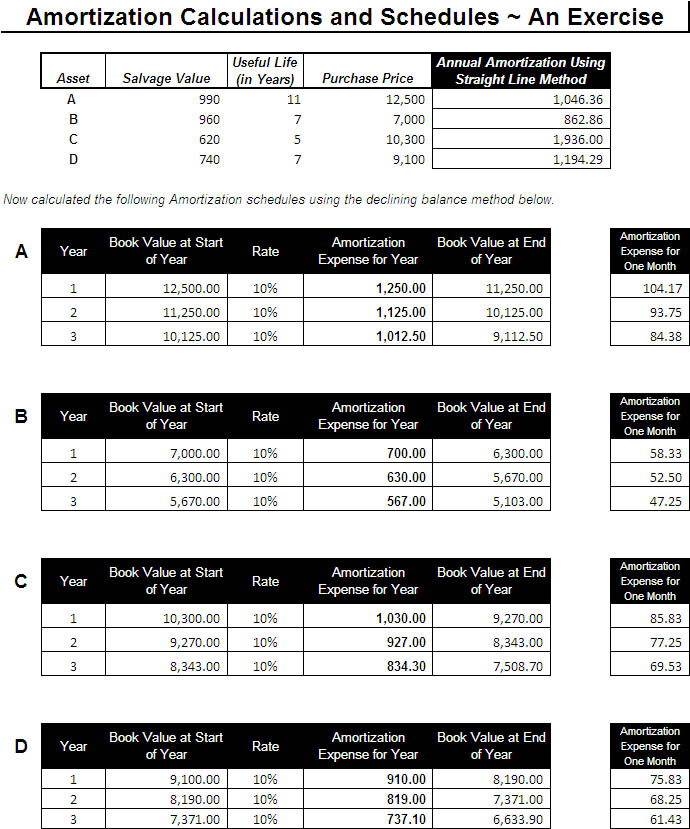

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

Practice

Exercise - Do it on your

own first!

Complete the following chart of amortization

schedules.

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

Answer

- Do it on your own first!

back

to top